In the article, he says,

For me, as for others, the Net is becoming a universal medium, the conduit for most of the information that flows through my eyes and ears and into my mind. The advantages of having immediate access to such an incredibly rich store of information are many, and they’ve been widely described and duly applauded. “The perfect recall of silicon memory,” Wired’s Clive Thompson has written, “can be an enormous boon to thinking.” But that boon comes at a price. As the media theorist Marshall McLuhan pointed out in the 1960s, media are not just passive channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought. And what the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation. My mind now expects to take in information the way the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.

Carr explains that his fear is rooted in past evolutions of the human brain when it has come in contact with new technology. When writing became more common, Socrates (in Plato's Phaedrus) fretted that people would “cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful.” And they did.

When Gutenberg’s printing press arrived in the 15th c., scholars worried that the "easy availability of books would lead to intellectual laziness, making men 'less studious' and weakening their minds." And they were right, too.

When Friedrich Nietzsche, his sight failing, started composing on a typewriter in 1882, his friends noticed that his writing style changed. Nietzsche concluded that “our writing equipment takes part in the forming of our thoughts.”

Even though each of this historical changes in how we communicate brought with them great, unanticipated blessings, Carr remains uneasy because the internet seems to rob us of the ability to read deeply:

The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas. Deep reading, as Maryanne Wolf argues, is indistinguishable from deep thinking.

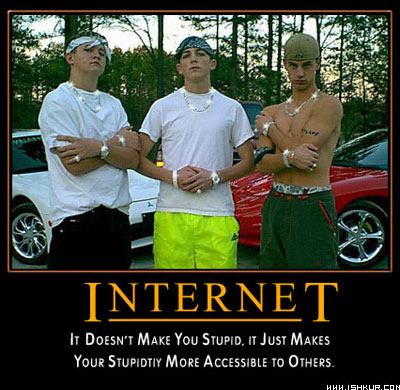

You can read the entire article at Atlantic.com. For counter-argument, we refer you to the poster below:

Poster credit: parody of Despair.com's "Successories" created by Ishkur.com.

Poster credit: parody of Despair.com's "Successories" created by Ishkur.com.

ms.dsk is reading

ms.dsk is reading  Rob Koelling is reading

Rob Koelling is reading  S. Renee Dechert is reading

S. Renee Dechert is reading  Mary Ellen Ibarra-Robinson is reading

Mary Ellen Ibarra-Robinson is reading  Bill Hoagland is reading

Bill Hoagland is reading  Jennifer Sheridan is reading

Jennifer Sheridan is reading  Robyn Glasscock is reading poetry by

Robyn Glasscock is reading poetry by  Susan Watkins is reading

Susan Watkins is reading

No comments:

Post a Comment